The past few weeks have seen a cascade of misdeeds to fascinate self-appointed apology-watchers like me.

Where to begin?

There’s the scandal over the $820,000 taxpayer-funded junket to Las Vegas in 2010 by the General Services Administration (GSA). And the even seamier “hookergate” involving members of the Secret Service (though at least they were price-conscious in their indiscretion).

There was also plenty of outrage over ill-chosen public comments last month. In an unexpected gift to the Romney campaign, progressive pundit and PR advisor Hilary Rosen managed to anger stay-at-home moms, conservatives, and even the White House with her comment about Ann Romney. Then there were the rogue remarks of unapologetic rocker and gun enthusiast Ted Nugent, whose wacky anti-Obama rant earned him a visit from the Secret Service—in a nice bit of symmetry.

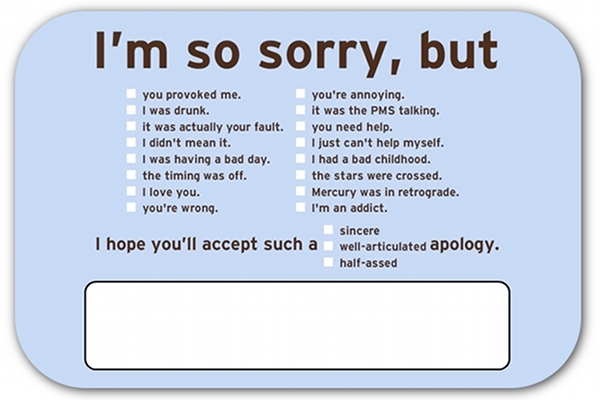

Most of these incidents resulted in a public mea culpa. Some are baffling and nearly all are terrible. Inspired by the past week of apologies, I’ve drafted a guide for how not to deliver a face-saving public apology:

Wait it out. This is what Hilary Rosen tried to do in the wake of a strong reaction to her statement that “Ann Romney hasn’t worked a day in her life.” Though Rosen explained she was objecting to candidate Romney’s attempt to liken his wife to struggling working moms rather than criticizing her choice, the controversy didn’t abate until she formally apologized. Politics? Of course, but if you live by the sword, sometimes you have to fall on it.

Blame the victim. “I’m sorry if anyone was offended….” is how the classic non-apology starts. This is a flawed communications strategy because it evades responsibility and seems to put the blame on the injured parties. There’s a bit of this in Romney adviser Richard Grenell’s public apology for his Twitter updates criticizing Hillary Clinton’s appearance, Rachel Maddow’s style, and Callista Gingrich’s hair, among others.

“I apologize for the hurt (the tweets) caused,” reads Grenell’s statement. A more sincere message would have gone something like this: “I attacked people in petty and personal ways because I don’t like their politics, and that is immature and wrong.”

Blame the system. Similarly, pointing fingers at forces beyond your control to deflect responsibility is unlikely to be effective. Disgraced former GSA head Martha Johnson tries to have it both ways in her apology. She accepts responsibility but spends more time explaining that the infamous Vegas junket was well underway when she was appointed and that she was “unaware of the scope.” Weak.

Make it about you. Johnson goes further by expressing sincere regret for the GSA fiasco. Her words are affecting—until the end: “I will mourn for the rest of my life my failed appointment…” It should be more about the taxpayers, not her career.

Similarly, in Rush Limbaugh’s apology to Sandra Fluke for calling her a “slut,” he spends the bulk of his statement justifying his own outrage over the contraception issue, then ends with the single line, “I sincerely apologize to Ms. Fluke for the insulting word choices.” Not enough, Rush.

Make light. Humor (of the self-deprecating variety) can occasionally work, but it’s highly risky and must be deployed with extreme caution. An exception to the “no humor” rule, and my favorite use of self-deprecation, might be Robert Scoble’s blunt and refreshing self-indictment for an opinionated rant against an unsuspecting online commenter last year. Scoble was man enough to drink his own (apology-flavored) Kool-Aid in a blog post titled, “How I Made Myself Into An A-Hole.” Well said.

Source: [PR Daily]